Always being conscientious

I become quickly aware of when I’m not doing something quite right. It is not obvious, but it is a definite feeling, a knowing that people are looking at me curiously and sometimes judgmentally from the side of their gaze. These norms are so fully embodied and followed by nearly all people that if you do not know, it is immediately noted by others. I clumsily catch on and try to keep up. My indoctrination into norm behaviors has been somewhat swift.

No walking and eating. Raghav and I had read about this prior to going. Also, we had a few Americans tell us about their (embarrassing) experiences when they committed this faux pas in their travels in Japan. We found this practice to be alive and well upon arrival. You do not walk and eat. If there is street food, there will often be a crowd around the food stalls where they purchased their food and are now diligently eating and finishing it there.

Carry and bring your trash back home with you. There are not many public trash cans. In fact, visitor-heavy areas will sometimes have signs informing people to bring their trash home with them. At Yokohama Chinatown, there was an avenue of street food stalls - and not a single public garbage. Since I had come across this before, I knew enough to put my garbage in my backpack to throw away at home.

Subway surfing. People do not like to touch the poles, the hand holds, or really any part of the train if they can help it. There are a lot of subway surfers.

No crossing the street if the walk sign is red. Even if there is not a single car in sight, nowhere to be seen, do not cross! Even when crossing a narrow street that is literally only three steps wide, do not cross until the signal says so.

The many observed norms are in part what keeps both public and private spaces so clean, orderly, and well-maintained. It is also a social organizer. People have a strong sense of their culture and how to do things the proper way, from the most general to the most specific kind of task. This is reflected in the language too. Many passing phrases that are casual in the US seem to have specific and sometimes honorific ways of saying them here in Japan.

It is undeniable that these strong norms are source of tension for me when I go out for errands and activities. There are many norms that I am still figuring out the hard way. Also, I am unaccustomed to people I don’t know being invested in how I do things.

Kamakura, a town of temples and shrines

Raghav and I traveled to Kamakura, a little less than an hour from where we are in Yokohama. The train system continues to impress. It conveniently brings us really anywhere we’d think to go. We use a single transit card called suica that we can scan across different transport systems and cities.

Kamakura is a seaside city southwest of Tokyo and Yokohama. There is a Buddhist temple or a shintō shrine every few blocks in the city area. We visited four temples that were all founded in the late 13th to early 14th century: Kōtoku-in, Hasadera, Engaku-ji, and Hokokuji with a bamboo forest. We rented bikes for the day and biked to each temple, weaving through the narrow and intimate side streets of Kamakura.

Buddhism and Shintoism

Buddhism came to Japan around the 6th century. Shintoism is thought to be Japan’s oldest religion, very much predating Buddhism. Shintō beliefs center around spiritual beings or gods of the natural world and of sacred geographic locations. There is noticeable mixing of Buddhist and shintō beliefs and practices in Japan, and this mixing apparently dates back centuries. At Buddhist temples there are idols of shintō gods, like the tengu in the temple on Mt. Takao. Many temples also have purification fountains to wash hands even though these are originally part of shintō ritual.

The Buddhist place of worship, otera, is referred to as a temple, loosely translated. It has pagodas, incense burners, Buddhist statues, a temple bell, and an entrance gate. A shintō place, jinja, is referred to as a shrine, loosely translated. Although I read that it more specifically refers to the sacred geographic location where the structure is then constructed to mark it. It may have a torii gate, guardian dogs at the entrance, a purification fountain, and woven straw rope to mark sacred objects, shimenawa. There was shimenawa wrapped around the thousand year old tree that I posted a photo of in my previous newsletter.

Even as I look to distinguish Buddhism and Shintoism, I don’t know how useful it is to frame the belief systems separately. After seeing a number of temples and shrines, they seem indelibly interconnected and part of a hybrid belief system and practice unique to Japan.

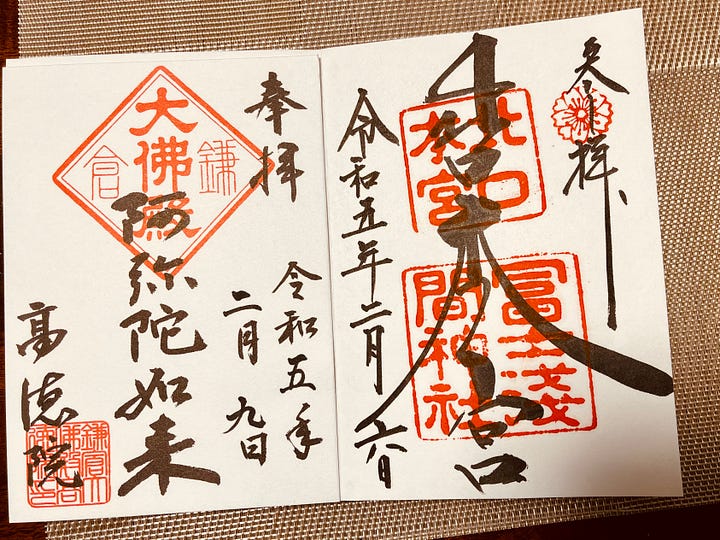

Goshuinchō: A book of seals

Goshuinchō is a bound book to be filled with seals or stamps from temples and shrines visited. We each purchased a goshuinchō on top of Mt. Takao, and have collected stamps at each temple that we have visited since. There is a nominal fee paid to the attendant who writes in calligraphy and also stamps the temple name, the date in the traditional Japanese calendar, and the word for worship (奉拝 “houhai”). The year is different in the traditional Japanese calendar, based on the reign of the emperor.

Funny little things

スパチキ (“Supa chiki”). This is the name of a spicy chicken sandwich at McDonald’s. “Supa” is not for “super,” which is what I initially thought. “Supa” is short for the English word “spicy” as Japanese people pronounce it: “su-pai-shii.” “Chiki” is short for chicken. I didn’t say this with conviction when I ordered, feeling a little foolish, and this led to confusion with the cashier. One of many instances of half-hearted pronunciation on my part that caused miscommunication.

Ice-cold public bathroom sink water and nowhere to dry. A number of public bathrooms have only ice-cold tap water for hand-washing. I’ve noticed that most Japanese women carry around their own handkerchief for hand drying. It brings me back to my childhood when my mom always had one or two handkerchiefs on hand. It can be quite uncomfortable walking out into the cold weather with ice cold hands! I have since acquired my own handkerchief that I bought at a Mt. Fuji souvenir shop.

Konbini conversating. Without fail, every time we go into a konbini to buy a snack or drink, I am fumbling with my Japanese at the cashier. At times I have no idea what they’re asking me. Cashiers use a “humble” Japanese speech that is hard for me to follow. Also, it feels like they ask me a new question every time I go in. And actually, I have discovered that this is partly what’s happening. Depending on what specific item I purchase, I will be asked different questions at the counter. With some desperation, this week I googled, “what is said at japanese konbini check out,” and found a very detailed, line by line, konbini check out dialogue. It turns out, it’s more complicated than you’d think! If curious, you can read details here.

Tōryanse at crosswalks. Similar to the US, in Japan you can press a button at the crosswalk to signal that you want to cross the road. I pressed this button. The walk signal eventually changed to green, and as it did a hauntingly beautiful melody began to play from the tinny, crosswalk speaker. It caught me off guard and I later googled it. I learned that this song is a children’s song called Tōryanse. This made some sense to me because two people behind me at the crossing had sang along to the instrumental melody. It was clearly a known song.

Below I embedded an audio clip of Tōryanse sung by the May Music Factory whose YouTube channel I came across here.

Until next time.

It seems you are adjusting as quickly as you can to the very nuanced daily norms in Japan. I imagine it's a lot to learn, some of which comes through trial and error. You and Raghav are both such observant and thoughtful travelers!

I don't think any native English speaker could truly feel comfortable saying "Supa chiki" with conviction lol

And the crosswalk music would've definitely scared me! :)